Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2023) Volume 17, Issue 9

Relational triplet: Vital satisfaction, social support and depression in cancer female breast

Badr El Marjany1, Fouad Ech Chouyekh2*, Zakaria Badri3,4, Sofia Jayi2, F.Z Fdili Alaoui2, Hikmat Chaara2, Abdeliah Melhouf2 and Smail Alaoui2,52Hassan II University Hospital of Fes, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Dentistry, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco

3Higher School of Education and Training, Psychology, Hassan I University, Settat, Morocco

4Faculty of Educational Sciences, Mohamed V University, Rabat, Morocco

5Department of Psychology, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences-Dhar, El Mahraz-Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco

Fouad Ech Chouyekh, Hassan II University Hospital of Fes, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Dentistry, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco, Email: fouad.echchouyekh@usmba.ac.ma

Received: 27-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. OAR-23-108218; Accepted: 27-Aug-2023, Pre QC No. OAR-23-108218 (PQ); Editor assigned: 30-Jul-2023, Pre QC No. OAR-23-108218 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Aug-2023, QC No. OAR-23-108218 (Q); Revised: 22-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. OAR-23-108218 (R); Published: 05-Sep-2023

Abstract

This work aimed to evaluate the relationship between life satisfaction and social support and the impact of these parameters in depression in women with breast cancer.

Patients and methods: The sample of this study is composed of 96 Moroccan women. The participants completed a questionnaire composed of 3 scales measuring the variables of interest, adapted and validated for the Moroccan population (Scale of vital satisfaction: Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin, 1985/ Social Support Perception Scale: Vaux, Phillips, Holly, Thompson, Williams, & Stewart, 1986/ The Beck Depression Inventory: BDI-II; developed by Beck et al., 1996)

Results:

• The level of life satisfaction became significantly with the evolution of the disease (duration and stage).

• Women who express lower levels of life satisfaction suffer from higher levels of depression.

• Women who have a high level of social support are protected against the negative effect of a decrease in life satisfaction on depression.

Keywords

radionuclide, uranium, gamma-ray spectrometer

Introduction

The fight against breast cancer is a very trying process for patients, which can cause intense psychological damage, ranging from deep emotional distress to severe depression. Beyond the hard-to-bear physical sequelae it causes, breast cancer in fact upsets the life of a couple, the social, family and professional aspects of the lives of patients. whether when the disease is announced, during the treatment or after the period of care, certain variables such as social support and vital satisfaction then appear as main factors influencing the symptoms of depression in women followed for breast cancer.

Theaim of our study is to evaluate the impact of its parameters in depression in women with breast cancer.

Hypotheses

Taking all these aspects into account, we propose and test the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: Vital satisfaction decreases with disease progression (duration and extent of disease).

Hypothesis 2: Life satisfaction negatively predicts depression

Hypothesis 3: The negative impact of life satisfaction on depression occurs only at low levels of social support.

In summary, our study focuses on the role of cognitive and social variables such as vital satisfaction and the perception of social support in the psychological health of Moroccan women with breast cancer.

This is a new take on a sample that has received little attention.

Methodology

Participants and procedure

Before proceeding with this study, the researchers obtained the authorization of the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of Oujda (CERBO) of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of the University Mohammed 1 of Oujda and the General Management of the University Hospital Centre of Fez (CHU Fez), which approved the study procedures and consents, and granted access to the target population to CHU Fes hospital of the first 120 women, 24 participants were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. The final sample of this study is composed of 96 Moroccan women, 25% of whom are between 18 and 30 years old, 46% between 30 years and 45 years old and 30% over 46 years old

85% of women have a medium-low level of education and only 25% have completed university studies. Regarding the family situation, 43% of the participants are married, 21% single, 23 divorced and 13% widowed. 69% of participants live in urban areas and 31% in rural areas.

Theparticipants completed a questionnaire composed of 3 scales measuring the variables of interest, adapted and validated for the Moroccan population.

The questionnaire was administered by a single collaborator (responsible for following ethical procedure guidelines approved by the ethics committee) individually and anonymously in a primary care ward while participants waited their turn to perform an X-ray test. To answer the entire questionnaire, the women took between 15 and 25 minutes. Theinclusion criteria had to be a Moroccan woman, having suff red from breast cancer. All participants gave their consent to participate.

Tools

• Questionnaire measuring socio-demographic variables: the women indicated their age, level of education, place of residence, family situation and duration of illness and location of illness.

• Scale of vital satisfaction. Adapted to Arabic by AyyashAbdo and Sánchez-Ruiz, (2012) and to the Moroccan context in the adolescent population by El ghoudani et al., (2020). The scale focuses on the cognitive assessment of how satisfi d a person is with their life in general. The original scale is composed of 5 Likert-type items, with a response range of 7 points (1, totally disagree; 7, totally agree). The internal consistency is α= .86.

• Social Support Perception Scale adapted and validated for the Moroccan context. This instrument assesses the perception of the relationship maintained with others. It contains a total of 23 items, which group together three subscales, depending on the origin of the support: family α= .86, friends α= .80 and people (others) α= .84, forming a general index of social support α = .93. Thescale is scored using four response alternatives, ranging from totally agree to totally disagree.

• TheBeck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; developed by Beck et al., 1996) adapted into Arabic by Hamdi Abdallah, (2013) and adapted to the Moroccan context for the adolescent population (BDI-IA. AL-MA) by Alaoui et al., (2021) to measure depressive symptoms and their intensity. The adapted version consisted of 21 items, with a 4-point Likert type response format (from 0 normal to 3 more severe). The reliability index reported in the various studies varies between 0.89 and 0.93 and in the present study α= .87

Results

For the analysis of the results, we used the statistical package IBM SPSS V.20 and process v. 3.4 for mediational analyses.

To answer the first hypothesis and check whether or not life satisfaction decreases with the progression of the disease, analyzes of variance (one-way ANOVA) were carried out to check if there were signifi ant diff rences in the levels of satisfaction. of life depending on the duration of the disease and its stage.

The results show that the level of life satisfaction is signifi antly lower in women who have had the disease for more than 6 months than in women who have had it for less than 3 months. (F (2, 95)=5.306; p= 0.007)) (see Table 1), in terms of disease stage, although the results were not statistically signifi ant (t(94)=1.78; p= 0.077), though levels of vital satisfaction tend to be lower in women who are at an advanced stage of the disease than in women who still have an early stage (M=13.31, SD=4.60 vs. M=15.19, SD=5.52).

Tab.1. Mean (M) y standard deviation (SD) in vital satisfaction by disease duration

| Duration of illness | Vital Satisfaction M(SD) |

|---|---|

| Less than 3 months | 17.75 (5.65) |

| Between 3 to 6 months | 15.17 (5.41) |

| More than 6 months | 12.94 (4.45) |

To answer the second hypothesis, which consists in verifying whether there is a signifi ant correlation between vital satisfaction and depression, a Pearson correlation analysis was carried out, and the results show that there is a statistically signifi ant negative correlation between both variables (r = -.379, p<.05). Women who express lower levels of life satisfaction suff r from higher levels of depression. Moreover, and through a linear regression analysis, we verifi d that vital satisfaction signifi antly predicts levels of depression, so a decrease in levels of vital satisfaction would lead to an increase in levels of depression. (β=0.379; corrected R2=0.134; change in F=15.71; p<0.01).

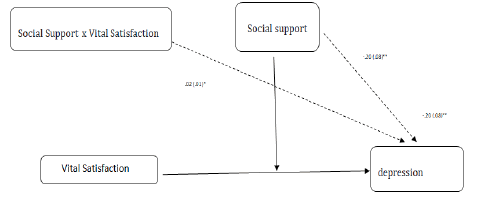

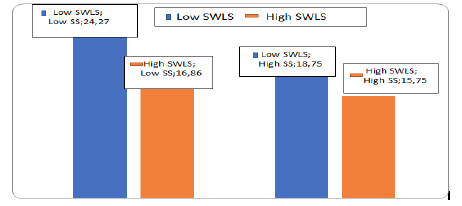

Finally, to test our hypothesis on the moderating eff ct of the social support variable on the relationship between life satisfaction and depression, we performed a moderation analysis using the macro Process, the results obtained state that there is an interaction between vital satisfaction and social support (B=0.02 (0.01); t = 2.40; p = 0.018) (see Figure 1), and as shown in Figure 1, decreasing life satisfaction only predicts increased levels of depression at low levels of social support, but not at high levels of social support. Th refore, social support blocks the negative eff ct of decreased life satisfaction on depression. Social support is a protective factor in Graph 1.

Figure 1: Social support moderating the effect of life satisfaction on depression in women with breast cancer

Graph 1: Levels of depression according to vital satisfaction and social support

Women who have a high level of social support are protected against the negative eff ct of a decrease in life satisfaction on depression.

Discussion

Breast cancer is an experience that can turn the patient's life upside down and call into question her feminine identity.

The experience of the disease from diagnosis to treatment with its side eff cts puts patients in front of problems, in addition to the physiological eff cts of the disease, which alter the vital satisfaction of patients in its physical dimensions, psychological and social; this alteration lasts even after the end of the treatment. All of these problems can inhibit psychosocial adaptation and lead to a reduction in quality of life [1-3].

This impact on vital satisfaction can be noticed from the onset of the disease and worsens over time. This is the case of our study which showed that the level of life satisfaction is signifi antly lower in women who have the disease for more than 6 months than in women who have had it for less than 3 months. (F (2, 95)0=5.306; p= 0.007)), in addition to the duration, several aspects related to the disease (the site, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and induced menopause, etc.) perceived by the patient as physical and psychological transformations represents a real psychological distress which aff cts the quality of life, in our study we were interested in the stage of the disease which objectifi d, although the results are not statistically signifi ant (t (94)=1 .78; p = 0.077) that levels of vital satisfaction tend to be lower in women who are at an advanced stage of the disease than in women who still have a localized stage (M=13.31, SD = 4.60 vs. M = 15.19, SD = 5.52).

So our results highlighted a pejorative impact of the duration and the stage of the disease on the overall quality of life, these data have also been confirmed by the study of P. Brunault, et al. who found that the deterioration in quality of life, especially physical, was predicted by several factors (R = 0.600; adjusted R2=0.332;F[5.109] = 12.3), including the tumour stage according to stage T of the TNM classifi ation, on the other hand the reviews of the literature by Mols et al. and Bloom et al. mounted a low impact of baseline tumour characteristics on long-term quality of life [4-6].

According to the study by Alfano CM et al, women with breast cancer face problems that go beyond the physiological eff cts of the disease, and that may inhibit psychosocial adjustment and lead to reduced quality of life, and this, for several years after the end of treatment [7].

Our study also confirmed that there is a close relationship between vital satisfaction and risk of depression in cancerous women, something that is also confirmed by the study by P. Brunault, et al, showing that patients with a depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder had a signifi ant impairment in their overall quality of life and of these diff rent facets (physical and emotional) [4].

This disorder (depression) is underdiagnosed and undertreated, although Prevalent according to study by Osborn RL et al, despite psychotherapeutic treatments and eff ctive pharmacological [8-10].

Theprevalence of depression was 37% in the study in 100 Tunisian women with breast cancer that can predict and worsen the quality of life so to overcome this depression disorder in order to off r support adequate, better detection of this disorder is necessary [10].

The level of depression varies according to the degree of life satisfaction and above all also linked to social support, the latter illustrated in our study as a protective factor such that women who benefit from a high level of social support are protected against the negative eff ct of a decrease in life satisfaction on depression

This concept of social support appeared in the 1970s, with articles by Caplan (1974), Cassel (1976) and Cobb (1976). According to Caplan (1974), social support is provided by relatives but also by the community or neighbourhood. It aims to protect the wellbeing of individuals in the face of various stressors. For Cassel (1976), support is essentially provided by the close environment and aims to protect individuals faced with stressful events. Cobb (1976) considers social support as information leading the person to believe that he is appreciated and loved, that he is valued and that he is part of a network with mutual obligations. So we see that social support was first defined through its function. It was also reduced, initially, to its sociological dimension of social network, that is to say to the "number of social relations that an individual has established with others, the frequency of eff ctive social contacts with these people and the intensity (or strength) of these links.” For Cohen and McKay (1984), it would be a psychological resource that brings together all of a subject's perceptions regarding the quality of his social relations. We therefore speak of perceived social support. A very extensive social network may very well not meet the needs of an individual, just as a single person may provide the desired assistance in a painful situation. It is the perception of reality that is important, more than reality itself. We already see that the proposed definitions are very diverse and often built around the functions and dimensions that make up this concept.

It is also important to distinguish between diff rent types and diff rent sources of support. Th re would be four types of support:

• Emotional support is the protection and reassurance given to a person • The support of esteem consists in reassuring a subject concerning his skills, his value;

• Material or financial support can be provided through loans, donations of money and any service rendered;

• Informative support consists of giving advice, making proposals or providing information on the questions the person is asking.

It seems important to us, first of all, to describe the needs of the patients in terms of social support. Faced with the feeling of uncertainty generated by a cancer diagnosis, patients express many needs: first of all to understand what they are going to have to face, but also to be supported and reassured in the face of this threatening life event.

Another important element of social support is the source. Support can be provided by spouse, family, friends, colleagues, or health professionals.

In Ellouze Faten's study of 100 Tunisian women with breast cancer the source of family support was a protective factor for body image disorder in univariate analysis: 94% of women had real support family emotional (compassion and caring) and material (providing the cost of care and support for children) the needs diff r according to the sources of support: patients with breast cancer expect empathetic support from everyone in their network, but informative support is more welcome if it is provided by professionals of health only if it comes from family or friends, something that was also confirmed by the study concerning the perception of emotional support and informative support as he noted, that it decreases over time, that patients have expressed the need for them to have recourse to support outside the family unit, from professionals (doctor, nurse, psychologist) or peers (speaking group, etc.) [9, 10]. However, it is important that these needs are met because the more patients report needs in terms of support, the more they report high levels of distress, as well as their partner if they live as a couple.

However, the view of cancer in society and breast cancer in particular, seems to have evolved and most patients now report a high level of satisfaction with the support received. And this is all the more important since patients who are satisfi d with their social support adjust better to their cancer, whatever its stage.

Theadequacy between the support wanted and the support received is very essential, it is associated with a good adjustment of patients treated for breast cancer, while receiving unwanted support is associated with poor psychosocial adjustment. Hodgkinson et al. (2007b) are precisely interested in the needs of patients in terms of support and the satisfaction of these needs. Th y included in their study 170 patients who had been diagnosed with breast cancer between two and ten years earlier. 2/3 of patients say that some of their needs in terms of social support have not been met. A quarter of patients say that their information needs have not been met, but most often these needs are inherent in the period of remission. These results have been confirmed by numerous studies. Those of Cappiello, Cunningham, Knobf and Erdos (2007) consisted in questioning 20 patients on average two years after their treatments for breast cancer on their possible remote needs for these treatments. Patients mainly ask for informational support regarding the lingering eff cts of treatments, possible symptoms of emotional distress and lifestyle changes. Indeed, 45% of them say they have not received any information on the transition phase of treatment / remission.

According to Dunkel-Schetter and Wortman (1982), the attitudes of others towards cancer patients are influenced by two factors: by a set of ambivalent feelings and attitudes towards the patient and by representations or beliefs concerning the way in which one should behave in front of a sick person (social norm). Many people think it is inappropriate to talk to a patient about the disease because it could lead to depressive symptoms.

However, the view of cancer in society and breast cancer in particular, seems to have evolved and most patients now report a high level of satisfaction with the support received. And this is all the more important since patients who are satisfi d with their social support adjust better to their cancer, whatever its stage.

Conclusion

In summary, although research is needed to clarify which types of interventions would be particularly eff ctive and to verify their eff ct on depression in patients with breast cancer, the results of the present study indicate that clinicians should direct their patients more frequently to psychosocial resources, especially for patients who are less well supported and who present lower levels of vital satisfaction related to cancer.

References

- Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Persistence of restrictions in quality of life from the first to the third year after diagnosis in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4945-4953.

[Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich M. Depression and cancer: recent data on clinical issues, research challenges and treatment approaches. Curr opin oncol. 2008;20:353-359.

- Tarantini C, Gallardo L, Peretti-Watel P. Working after Breast Cancer. Stakes Constraints Outlooks Sociol. 2014;5:139-155.

[Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur j cancer. 2005;41:2613-2619.

- Bloom JR, Petersen DM, Kang SH. Multiâ?dimensional quality of life among longâ?term (5+ years) adult cancer survivors. Psychoâ?Oncology: J Psychol Soc Behav Dimens Cancer. 2007;16:691-706.

- Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, Bowen DJ, Sorensen B, et al. Physical activity, long-term symptoms, and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:116-128.

- Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. int j Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13-34.

[Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C. Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast cancer res treat. 2008;110:9-17.

- Naaman SC, Radwan K, Fergusson D, Johnson S. Status of psychological trials in breast cancer patients: a report of three meta-analyses. Psychiatry: Interpers Biol Process. 2009;72:50-69.

- Asma G, Amani Y, Rim A, Safia Y, Semia Z, et al. Body Image Disorder in Women Treated for Uterine Cancer. Women’s Health. 2020;20:556036.

[Google Scholar] [CrossRef]