Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2024) Volume 18, Issue 9

Translation and adaptation of the learning organisation survey for French speaking low middle income countries

Amalia Giuliani Diez1, Hajar Essangri1,2, El Houcine Akhnif3, Mohammed Anass Majbar1,2, Amine Benkabbou1,2, Laila Amrani1,2, Raouf Mohsine1,2 and Amine Souadka1,22Mohammed V University, Faculty of Medicine, Rabat, Morocco

3World Health Organization, Morocco

Amine Souadka, Department of Surgical Oncology, National Institute of Oncology, Rabat, Morocco, Email: a.souadka@um5r.ac.ma

Received: 02-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. OAR-24-147832; , Pre QC No. OAR-24-147832 (PQ); Editor assigned: 07-Feb-2024, Pre QC No. OAR-24-147832 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Feb-2024, QC No. OAR-24-147832; Revised: 01-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. OAR-24-147832 (R); Published: 29-Oct-2024

Abstract

The development and management of health policies in low and middle income countries is challenged by political and financial restrictions, requiring tailored strategies that health systems and policy makers in high income countries may not be able to offer. Evolving into a learning organization requires diagnostic tools to assess how well teams, departments and institutions are performing and help identify areas for improvement. The learning organization survey fulfils these goals through the building blocks.

The aim of this study is to translate the Garvin's et al. Learning Organization (LO) survey into French to evaluate French-speaking health organizations.

We used the Brislin modified reverse translation technique to translate the survey, before cross-culturally adapting the survey through a workshop of experts and a committee of judges with an index of the validity of IVC content ≤ 80%. We also examined the dimensions of the survey according to categorized groups of professions namely doctors and medical students and trainees, nurses and administration and technical staff.

The survey was conducted with a sample of 111 workers from the National Oncology Institute of Rabat, with responsiveness rate of 65%. The established validation criteria were exceeded with a good internal consistency, demonstrated by a cronbach alpha coefficient superior to 0.8 in each block. Variations between the different groups were noted in the different dimensions with the doctors group having higher scores.

The French version of the LO questionnaire demonstrated good psychometric properties to be considered a useful and reliable tool capable of objectively assessing learning organizations and setting areas for their improvement.

Keywords

Translation, Validation studies, Learning organization, Low and middle income countries, Health policy

Abbreviations

UHC: Universal Health Coverage; NIO: National Institute of Oncology: LO: Learning Organization

Introduction

In many low and middle income countries, the development and management of health policies and guidelines is affected by political, financial and human resource restrictions, yielding in nongeneralizable strategies that are difficult to implement. These challenges are even more pronounced since the main generators of knowledge on health systems in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) are institutions in High-Income Countries (HICs) with different priorities, which don’t necessarily respond to the needs of health systems in LMICs. That is why it is ever so important for LMIC health systems to develop a supportive learning culture in order to achieve their goals [1].

Evolving into a learning organization mitigates individualized and tailored strategies by building a ground for continuous adaptation and growth at an individual, team and organization level. As such, health care organizations’ capacity for innovation, adaptation and change to achieve evidence based practice, improved patient experience, cost efficiency and population health depends on their ability to become learning organizations. This can also be a further step towards universal health coverage and strengthening health systems which is particularly important in low and middle income settings, as it enables creating functioning health systems that put “what works” into practice and prevents draining limited resources and worsening of health inequities. Promoting organizational learning has also the potential of enhancing resilience-building potential of low and middle income countries in order to better prepare for, manage and learn from crises [2].

Learning organizations are those providing environments that foster continuous learning and where people enhance their capabilities to create, acquire and transfer knowledge, while modifying behaviors to reflect new knowledge and insights through experimentation, systemic thinking and open discussion of errors. These concepts, often used in business and corporate culture to gain a competitive advantage in a rapidly changing environment, are becoming key elements that influence the effectiveness and/or success in implementing interventions in different health care settings [3].

Developed by Garvin et al, the learning organization survey not only enables assessment of an organization’s learning characteristics but can also prompt action by identifying weaknesses. The tool measures organizational learning by examining three independent factors, namely supportive learning environment, concrete learning processes and practices and leadership behavior that provides reinforcement which are also referred to as the building blocks of the learning organization. The first building block is a supportive learning environment and includes subcategories assessing psychological safety, appreciation of differences, openness to new ideas and time for reflection.

Following, the second building block examines concrete learning processes and practices, including the experimentation, generation, collection, analysis and interpretation, education and training as well as the information transfer. The third building block is leadership that reinforces learning, including behaviors such as listening, providing resources and signaling through their own behavior the importance of applying those principles [4].

The aim of this study is to translate and adapt Garvin’s LO survey to the French language for use in French speaking low and middle income countries.

Materials and Methods

We followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) directive guidelines for observational studies. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Institute of Oncology waived the study from ethical approval since all candidates agreed to participate in this study anonymously.

Translation and adaptation procedure

Tool presentation: The LO survey is divided into three building blocks with each one representing an area of improvement and intended to determine for different levels (employees, teams, leaders) how the organization is performing (Table 1) [5-8].

Tab. 1. The building blocks of the learning organization.

| Building block | Distinguishing characteristics |

|---|---|

| BLOCK 1 A supportive learning environment |

Employees: Feel safe disagreeing with others, asking naive questions, owning up to mistakes, and presenting minority viewpoints Recognize the value of opposing ideas Take risks and explore the unknown Take time to review organizational processes |

| BLOCK 2 Concrete learning processes |

A team or company has formal processes for: Generating, collecting, interpreting, and disseminating information Experimenting with new offerings Gathering intelligence on competitors, customers, and technological trends Identifying and solving problems Developing employees’ skills |

| BLOCK 3 Leadership that reinforces learning |

The organization’s leaders: Demonstrate willingness to entertain alternative viewpoints Signal the importance of spending time on problem identification, knowledge transfer, and reflection Engage in active questioning and listening |

Translation and back-translation

The first step in the process was the translation of the English LO survey (En1) by means of the modified Brislin reverse translation technique. Two Moroccan translators fluent in English and French independently translated the original survey into French (Fr1), which was then back-translated into English (En2) by a native speaker. Some terms were adapted during the translation in order to maintain the same meaning and no items needed alteration during back-translation. The project coordinator was in charge of keeping note of words and expressions which could have lost meaning during back translation and discrepancies were discussed with the translators [9].

Judges committee/committee of experts

Both the translated and back-translated versions of the survey were discussed at a multidisciplinary commission including 10 staff members from the National Institute of Oncology (NIO). The degree of agreement between the specialists for each item was computed in the form of a content validity index (IVC), with an IVC of 0.72 considered as acceptable [10].

After adjustments, the Final French version (FFr) of the survey was generated and assessed in terms of conceptual equivalence, clarity and language before being forwarded to the general coordinator of the project for final approval [11].

Adaptation

The cultural adequacy of the FFr of the survey was assessed by an expert’s committee during which included 12 participants among which were professors, nurses, medical students and surgical residents, particularly selected for their experience at NIO. All participants received the workshop syllabus and material to be discussed one week prior.

On the day of the meeting, multidisciplinary groups containing a professor, nurse, medical student and surgical resident were assembled. An introduction to the concept was provided and each group was assigned a LO block. For each characteristic of the LO block, the groups were in charge of deciding, by common agreement, whether to maintain, remove or adapt the element. Once group discussions were over, each team presented their decisions to be discussed with the rest of the committee and a Pre-Final French Version (PFV) of the survey was validated with mutual agreement [12].

Final survey INO

At the end of this process, all 55 questions were kept in their respective blocks (Block 1 “Environnement learning favorable”; Block 2 “Processes and concrete learning practices”; Block 3 “Leadership that reinforces learning”), however the expert’s committee concluded in the need to change the reverse scoring from the original version to positive scoring, as it would be less confusing for respondents as well as analysis.

On the other hand, in 14 questions terms that are associated with the productive sector such as customers, managers and competitors were switched to health sector adapted terms, namely patients, supervisors and similar units. The concrete learning processes and practices block was the one with the maximum adaptation in the survey [13-15].

The rating scale categories were also changed with the options in the first two blocks varying on a 7 point Likert scale with 1 and 7 indicating total disagreement and perfect agreement respectively. As regards the third block, the agreement with each statement was expressed on a 5 point Likert scale with 1 and 5 standing for “never” and “always”.

Pilot test

The pilot study aimed to establish whether the questionnaire could be understood and completed by doctors, nurses, administrators and professors for the target population. As such, a group of 10 people were given the pre-final version to assess the need for modifications. The adjustment possibility was considered at 15% or more if participants had difficulty understanding or responding to an item of the instrument.

Setting

The study was conducted at the National Institute of Oncology (NIO) which is one of the central referral and teaching hospitals in Morocco with a staff capacity of 456 among which 46 doctors, 264 nurses, 32 technics, 40 administrative, 74 supporting staff alongside medical and nursing student from Mohammed Vth University of Rabat. The hospital has 169 beds, organized into 3 departments, namely surgery, clinical oncology and radiotherapy as well as an ambulatory chemotherapy unit. The number of admitted patients per year was 6489 in 2017.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Employees at the NIO (2) Present in the hospital in the period from 1st to 31st of August 2019 and (3) Willing to anonymously participate in the survey. The survey was randomly distributed to doctors, nurses, administration members as well as technical staff from several units and with different shifts. Workers who were absent or on vacation were excluded as well as support staff (security and cleaning due to their frequent rotation) [16].

Data collection

The survey was conducted anonymously and voluntarily; it was distributed to a random sample of 170 NIO staff members and responses were collected by members of the research team during August 2019. Descriptive variables of the population such as age, sex, status, years of experience in general and in the NIO as well as the unit each participant worked in were also collected [17].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed in mean and Standard Deviations (SD) while categorical variables were presented in percentage.

The normality test of the variables was calculated using Kolmogorov- Smirnov test of normality. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were used to assess reliability and internal consistency for each dimension, block and the entire survey.

Professions at NIO were grouped into three categories with group 1 including doctor, professor, resident and student; group 2 for nurses and group 3 for those with secretary, administration and technician jobs. The ANOVA test was used to compare descriptive statistics and the different blocks and dimensions of the survey. Data were analyzed using Excel® and IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0.

Results

Descriptive

Out of 170 distributed surveys, 111 were collected with a response rate of 65.2%. The survey was answered by a population of 67 women and 44 men, with a mean age of 31.17 ± 6.4. 36% of respondents were doctors, 48% (53) were nurses and 16% (18) were part of the administrative and technical staff. The mean years of total experience and the mean years of work at the NIO were 6.7 and 4.5 years respectively. The average response time was 12.2 min ± 3 min [18].

Reliability results

The NIO survey (n=111) showed excellent reliability with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.961. The independent reliability analysis for each block was also satisfactory with alpha Cronbach scores of 0.867, 0.949 and 0.916 for blocks 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Further details of the reliability analysis are presented in Table 2.

Tab. 2. Reliability (Cronbach's alpha).

| Cronbach's Alpha | |

|---|---|

| General | 0.961 |

| BLOCK 1 | 0.867 |

| Psychological safety | 0.703 |

| Appreciation of differences | 0.554 |

| Openness to new ideas | 0.703 |

| Time for reflection | 0.745 |

| BLOCK 2 | 0.949 |

| Experimentation | 0.888 |

| Information collection | 0.612 |

| Analyse | 0.672 |

| Education and training | 0.926 |

| Information transfer | 0.955 |

| BLOCK3 | 0.916 |

The mean of Q1 to Q55 was 2.55 ± 1.65 on Q42 to 5.45 ± 2.07 on Q5.

Question 5 on the sharing of knowledge being valued in the unit scored highest, while the lowest overall score was for statement 42 on the presence of forums in the unit for meeting with and learning from patients and citizens.

As regards the dimensions, the mean values ranged from 3.23 for the dimension on information transfer to 5.12 for the psychological safety dimensions. The total mean score for all dimensions is 4.82 ± 0.45 [19].

The mean values for each block ranged from 3.38 ± 1.03 (1.00 ± 5.00) for block 3 to 4.02 ± 0.63 (2.45 ± 6.60) for block 1. All statements fulfilled a good rating, with questions scoring higher than 2.0 indicative of a more supportive/suitable educational environment. The descriptive statistics for the survey statements are displayed in Table 3.

Tab. 3. Descriptive results for individual items, dimensions and blocks.

| Item | N | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Supportive learning environment | 4.82 ± 0.45 | ||

| Psychological safety | 5.12 ± 0.38 | ||

| Q1 | In this unit it is easy to express what you think | 111 | 5.06 ± 1.85 |

| Q2 | An error you make in this unit will not systematically be held against you | 110 | 4.5 ± 2.09 |

| Q3 | Members of this unit are often comfortable talking about problems and disagreements | 111 | 5.24 ± 1.66 |

| Q4 | Members of this unit willingly share information about what works and what doesn't | 111 | 5.37 ± 1.74 |

| Q5 | Knowledge sharing is valued in this unit | 109 | 5.45 ± 2.07 |

| Appreciation of differences | 4.92 ± 0.40 | ||

| Q6 | Differences of opinion are welcome in this unit | 111 | 5.31 ± 1.80 |

| Q7 | All opinions are valued in this unit, even those which are not in the majority | 109 | 4.57 ± 1.83 |

| Q8 | This unit tends to address differences of opinion directly with the group rather than doing so privately | 111 | 4.58 ± 1.84 |

| Q9 | In this unit people are open to other ways of working | 111 | 5.24 ± 1.60 |

| Openness to new ideas | 5.11 ± 0.30 | ||

| Q10 | In this unit. people appreciate new ideas | 111 | 5.36 ± 1.87 |

| Q11 | In this unit everyone listens and discusses new ideas | 111 | 5.17 ± 1.75 |

| Q12 | In this unit everyone listens and discusses new ideas | 111 | 5.27 ± 1.95 |

| Q13 | In this unit people are open to new approaches | 108 | 4.67 ± 1.84 |

| Time for reflection | 4.16 ± 0.42 | ||

| Q14 | People in this unit are not particularly stressed | 111 | 3.53 ± 2.039 |

| Q15 | Despite the workload, people in this unit find time to evaluate the progress of the work | 110 | 4.66 ± 1.88 |

| Q16 | In this unit deadline pressure does not prevent good work from being done | 109 | 4.21 ± 2.09 |

| Q17 | In this unit people have time to invest in self-improvement | 110 | 4.02 ± 2.03 |

| Q18 | In this unit we have time for reflection | 110 | 4.39 ± 2.09 |

| Block 2: Processes and concrete learning practices | 4.08 ± 0.53 | ||

| Experimentation | 4.47 ± 0.21 | ||

| Q19 | This unit frequently experiments with new ways of working | 110 | 4.70 ± 1.94 |

| Q20 | This unit frequently experiments with new products or services | 109 | 4.60 ± 1.84 |

| Q21 | This unit has a well-codified process for conducting and evaluating new experiments or new ideas | 108 | 4.22 ± 1.72 |

| Q22 | This unit frequently engages in short trial periods for the exploration of new ideas | 107 | 4.39 ± 1.94 |

| Information collection | 4.25 ± 0.48 | ||

| Q23 | This unit systematically collects information about similar units | 105 | 3.54 ± 1.95 |

| Q24 | This unit systematically collects information on economic and social trends | 107 | 4.63 ± 1.88 |

| Q25 | This unit systematically collects information on patients | 108 | 4.82 ± 1.62 |

| Q26 | This unit systematically collects information on scientific trends | 107 | 4.37 ± 2.05 |

| Q27 | This unit frequently compares its performance to other similar units | 106 | 3.84 ± 1.93 |

| Q28 | This unit frequently benchmarks its performance against top organizations | 106 | 4.35 ± 1.99 |

| Analyse | 4.54 ± 0.43 | ||

| Q29 | This unit is engaged in sometimes conflicting and productive debates during discussions | 110 | 4.04 ± 1.78 |

| Q30 | This unit seeks divergent opinions during discussions | 110 | 4.19 ± 1.84 |

| Q31 | This unit agrees to return to points of view already established during discussions | 109 | 4.60 ± 1.83 |

| Q32 | This unit frequently identifies and discusses underlying causes that may affect key decisions | 108 | 4.82 ± 1.62 |

| Q33 | This unit pays attention to different points of view during discussions | 110 | 5.08 ± 1.72 |

| Education and training | 3.92 ± 0.38 | ||

| Q34 | Newly hired employees in this unit receive adequate training | 110 | 4.10 ± 1.97 |

| Q35 | Experienced employees of this unit receive periodic training and continuing education | 108 | 3.82 ± 2.02 |

| Q36 | Experienced employees in this unit receive training when changing positions | 106 | 3.31 ± 2.16 |

| Q37 | Experienced employees in this unit receive training when new initiatives are launched | 106 | 4.14 ± 2.13 |

| Q38 | In this unit, training is valued | 110 | 4.43 ± 2.24 |

| Q39 | In this unit, there is time allocated for education and training activities | 110 | 3.76 ± 2.30 |

| Information transfer | 3.23 ± 0.31 | ||

| Q40 | This unit has meet and learn meetings with experts from other departments. teams or divisions | 109 | 3.53 ± 2.08 |

| Q41 | This unit has meet and learn meetings with experts from outside the hospital | 108 | 3.34 ± 2.05 |

| Q42 | This unit has meet and learn meetings with patients and citizens | 109 | 2.55 ± 1.65 |

| Q43 | This unit has meet and learn meetings with suppliers | 108 | 3.12 ± 1.94 |

| Q44 | This unit regularly shares information with networks of experts within the organization | 106 | 3.26 ± 2.06 |

| Q45 | This unit regularly shares information with networks of experts outside the organization | 108 | 3.15 ± 2.03 |

| Q46 | This unit quickly and accurately communicates new knowledge to key decision makers | 108 | 3.40 ± 2.01 |

| Q47 | This unit regularly carries out post-audit and post-action analyzes | 103 | 3.52 ± 2.01 |

| Block 3: Leadership that reinforces learning | 3.59 ± 0.63 | ||

| Q48 | My supervisors invite others to participate in discussions | 111 | 3.23 ± 1.49 |

| Q49 | My supervisors recognize their own limitations in knowledge. information or expertise | 111 | 3.41 ± 1.33 |

| Q50 | My supervisors ask in-depth questions | 110 | 3.48 ± 1.31 |

| Q51 | My supervisors listen attentively | 110 | 3.54 ± 1.41 |

| Q52 | My supervisors encourage diversity of points of view | 108 | 3.46 ± 1.36 |

| Q53 | My supervisors provide time. resources and space to identify organizational issues and challenges | 111 | 3.34 ± 1.36 |

| Q54 | My supervisors provide time resources and space to reflect on and improve past performance | 111 | 3.18 ± 1.32 |

| Q55 | My supervisors accept points of view different from their own | 110 | 5.14 ± 1.31 |

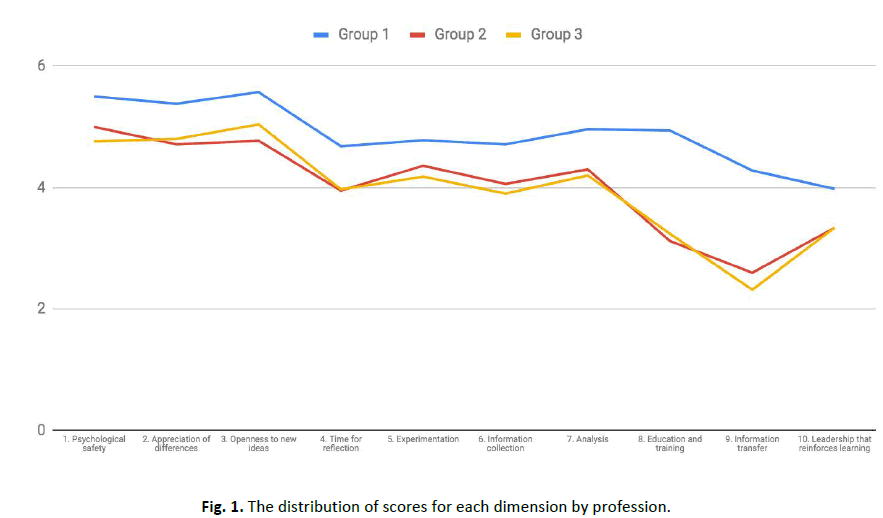

Scores for dimensions and blocks were categorized according to profession groups. Group 1 expressed relatively higher perceived levels of supportive learning environment (block 1), concrete learning processes (block 2) and leadership that reinforces learning significantly (block 3) in comparison to the groups 2 and 3 which showed no differences in the 3 blocks with p=0,17, p=0,001 and p=0,014 (Table 4).

Tab. 4. NIO perceptions about the Blocks (B) and Dimensions (D) among different groups of professions

| Profession | Variable | B1 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | B2 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | B3/D10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | N | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 32 | 37 | 34 | 37 | 35 | 36 | 38 |

| Mean | 5.25 | 5.5 | 5.38 | 5.57 | 4.68 | 4.67 | 4.78 | 4.71 | 4.96 | 4.94 | 4.28 | 3.98 | |

| SD | 1.06 | 1.2 | 1.17 | 1.4 | 1.43 | 1.29 | 1.66 | 1.18 | 1.38 | 1.72 | 1.59 | 1.03 | |

| Group 2 | N | 46 | 51 | 51 | 52 | 48 | 36 | 51 | 45 | 49 | 48 | 47 | 50 |

| Mean | 4.62 | 5 | 4.71 | 4.77 | 3.95 | 3.62 | 4.36 | 4.06 | 4.3 | 3.12 | 2.6 | 3.34 | |

| SD | 0.94 | 1.16 | 1.1 | 1.19 | 1.36 | 0.94 | 1.49 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.1 | |

| Group 3 | N | 17 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 19 | 13 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 18 |

| Mean | 4.74 | 4.76 | 4.8 | 5.04 | 3.97 | 3.62 | 4.18 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.24 | 2.32 | 3.34 | |

| SD | 1.07 | 1.58 | 1.24 | 1.02 | 1.34 | 1.16 | 1.42 | 1.1 | 0.98 | 1.82 | 1.71 | 0.91 | |

| P value | 0.17 | 0.068 | 0.061 | 0.01 | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.304 | 0.012 | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 |

Note: Group 1: Doctor, professor, resident, student; Group 2: Nurses; Group 3: Secretary, administrator, technician

The mean values for each professional category according to the dimensions range from 3.98 to 5.5, 2.6 to 5 and 2.32 to 5.04 for groups 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The distribution of scores for each dimension by profession.

Discussion

The objective of this study is to translate and validate the French version of the learning organization survey as an instrument for the evaluation of Moroccan health systems/departments learning organization. The Garvin’s survey translated into French showed satisfactory internal consistency and demonstrated its applicability for the evaluation of health learning organizations in Morocco [20].

Despite the urgent need for innovation, adaptation and change in health care, few tools enable the assessment of health care facilities as learning organizations or the effects of initiatives that require learning. Part of the difficulties regarding the assessment of organizational culture lies in the fact that instruments have been mainly developed for and tested in, enterprises and high-income settings in addition to the lack of well established and/or validated instruments for health organizations in low- and middle-income settings. The learning organization survey relies on supportive learning environment, concrete learning processes and practices and leadership behavior that provides reinforcement as main building blocks and potential areas for improvement.

Our findings indicate differences in scoring between profession groups on some of the dimensions. While the doctors group had higher scores for all characteristics of the learning organization, nurses and administration and technical staff groups scored lower, especially in the openness to new ideas and time for reflection dimensions. Similarly, variations between doctors and other groups have previously been noted in the assessment of the learning organization in other contexts and explanations such as the difference in academic level or the centralized hierarchical structure.

Another result that could be considered relevant is the doctor group highlighting a higher level of education and training compared to the other two groups. This is partially due to the continuous medical education medical staff is involved in contrast with nurses and other workers' lack of training opportunities [21-25].

Furthermore, the information transfer dimension demonstrated lower scores, which is indicative of the need of potential improvement. In fact, information transfer and knowledge sharing implies that individuals, groups and organizations can learn from each other and transforming individual experiences into actual learning is at the core of continuous improvement and part of the concrete steps of learning processes and practices. The predominant organizational structure for hospitals is, by tradition, mostly bureaucratic, with rigid rules and standard procedures and processes, which leaves a narrow margin for the transfer of information. Consequently, employees of lower academic levels have little or no influence on decision making and are mainly involved in specific guidelines. Although this structure is increasingly challenged, many hospitals and organizations, particularly in low and middle income countries, still continue with the traditional management policies. The stimulation of ideas exchange and the opening of boundaries through conferences, meetings and project teams either at crossorganizational levels or linking services, patients and suppliers however could be a step forward to ensure a fresh flow of ideas and perspectives [26].

On the other hand, all three groups agreed on the lack of reflection time, although it is the first step to fostering an environment of continuous learning and improvement of care.

Learning is difficult when employees are hurried, rushed or pressured by time t tends to be driven out by the pressures of the moment and dedicated reflection time should therefore be among the first measures of change [27].

Finally, the three groups marked a lack of leadership that reinforces knowledge. Management must be the first to change their behaviors. Since when people in power demonstrated through their own behavior; the willingness to entertain alternative points of view, openness to dialogue and debate and the importance of using time to identify problems, transfer information and reflections post-audits; people in the institution will be more encouraged to learn and offer new ideas and options [28-32].

The two dimensions that scored the highest value were those related to psychological safety and opening to new ideas which are key determinants of learning capacities and team values. These findings could be attributed to good leadership and positive interpersonal climate and represent a favorable ground for the learning organization [33-36].

Although our study is the first French validation of the learning organization survey, we are aware of some limitations. Firstly, the survey was not conducted by all the staff of the NIO as some were unavailable, on vacation or simply did not complete it. Furthermore, the support staff, namely security and cleaning, were also not included due to the frequent changes in their rotations and the fact that they are in the institution for short periods of time. On the other hand, the prominent hierarchical structure may hinder participants' willingness to express themselves freely due to confidentiality concerns and fears of retribution which could challenge the credibility and validity of the results [37-39].

Conclusion

The results of this study support the use of the learning organization survey as a reliable instrument to evaluate health organizations in French speaking low and middle income countries. These results could be translated into concrete actions, such as intervention programs to integrate and strengthen shared vision and team learning as well as enhance organizational effectiveness in areas where there is a need for improvement.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the director of the hospital Dr. Jawad Belahcen, who accompanied this project. Also a big thanks to all the units of the National Institute of Oncology of Morocco and specially the Digestive Surgical Oncology team.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author’s Contributions

GD and EA conceptualized the study. AGD, MAM, AS conducted data collection. AGD, AS and EH performed data analysis and prepared the first draft. All authors contributed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Akhnif E, Kiendrebeogo JA, Idrissi Azouzzi A, Adam Z, Makoutode CP, et al. Are our ‘UHC systems’ learning systems? Piloting an assessment tool and process in six African countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:1-4.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akhnif E, Macq J, Idrissi Fakhreddine MO, Meessen B. Scoping literature review on the learning organisation concept as applied to the health system. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:1-2.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Birleson P. Learning organisations: A suitable model for improving mental health services? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:214-222.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castaneda DI, Manrique LF, Cuellar S. Is organizational learning being absorbed by knowledge management? A systematic review. J Knowl Manag. 2018;22:299-325.

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:S31-S34.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devdutta Sangvai, Michelle Lyn, Michener L. Defining high-performance teams and physician leadership. Physician Exec. 2008;34:44.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edmondson AC, Kramer RM, Cook KS. Psychological safety, trust and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches. 2004;12:239-272.

- English M, Irimu G, Agweyu A, Gathara D, Oliwa J, et al. Building learning health systems to accelerate research and improve outcomes of clinical care in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001991.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gagnon MP, Payne-Gagnon J, Fortin JP, Pare G, Cote J, et al. A learning organization in the service of knowledge management among nurses: A case study. Int J Inf Manag. 2015;35:636-642.

- Garvin DA. Building a learning organization. Business Credit-New York. 1994;96:19.

- Garvin DA. Learning in action: A guide to putting the learning organization to work. Harvard Business Press, 2000.

- Garvin DA, Edmondson AC, Gino F. Is yours a learning organization? Harv Bus Rev. 2008;86:109.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jayatilleke N, Mackie A. Reflection as part of continuous professional development for public health professionals: A literature review. J Public Health. 2013;35:308-312.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones PS, Lee JW, Phillips LR. An adaptation of Brislin’s translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs Res. 2001;50:300-304.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalbarczyk A, Rodriguez DC, Mahendradhata Y, Sarker M, Seme A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to knowledge translation activities within academic institutions in low-and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:728-739.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotter JP, Cohen DS. The heart of change. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 2002.

- Kumar JK, Gupta R, Basavaraj P, Singla A, Prasad M, et al. An insight into health care setup in national capital region of India using Dimensions of Learning Organizations Questionnaire (DLOQ)-A cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC01.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lane J, Andrews G, Orange E, Brezak A, Tanna G, et al. Strengthening health policy development and management systems in low-and middle-income countries: South Africa's approach. Health Policy Open. 2020;1:100010.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leufven M, Vitrakoti R, Bergstrom A, Kc A, Malqvist M. Dimensions of Learning Organizations Questionnaire (DLOQ) in a low-resource health care setting in Nepal. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lord M. Group learning capacity: The roles of open-mindedness and shared vision. Front Psychol. 2015;6:150.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naimoli JF, Saxena S. Realizing their potential to become learning organizations to foster health system resilience: Opportunities and challenges for health ministries in low-and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33:1083-1095.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newell S. Knowledge transfer and learning: Problems of knowledge transfer associated with trying to short-circuit the learning cycle. J Inf Sys Tech Manag. 2005;2:275-289.

- Nicol JS, Dosser I. Understanding reflective practice. Nursing standard: Official newspaper of the Royal College of Nursing. 2016;30:34-42.

- O'Neil J. Participant's guide for interpreting results of the dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2003;5:222-230.

- Osterman KF, Kottkamp RB. Reflective practice for educators: Professional development to improve student learning. Corwin Press, 2004.

- Pantouvakis A, Mpogiatzidis P. The impact of internal service quality and learning organization on clinical leaders' job satisfaction in hospital care services. Leadersh Health Serv. 2013;26:34-49.

- Malloch K, Porter-O'Grady T. Quantum leadership: A resource for health care innovation.

- Moilanen R. Diagnosing and measuring learning organizations. Learning Org. 2005;12:71-89.

- Ridde V, Yameogo P. How Burkina Faso used evidence in deciding to launch its policy of free healthcare for children under five and women in 2016. Palgrave Communications. 2018;4.

- Rose RC, Kumar N, Pak OG. The effect of organizational learning on organizational commitment, job satisfaction and work performance. J Appl Bus. 2009;25.

- Senge P. Theffth discipline: The art and practice o/the learning organization. New York. 1990.

- Sheikh K, Agyepong I, Jhalani M, Ammar W, Hafeez A, et al. Learning health systems: An empowering agenda for low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2020;395:476-477.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singer SJ, Moore SC, Meterko M, Williams S. Development of a short-form learning organization survey: The Los-27. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:432-459.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souadka A, Benkabbou A, Al Ahmadi B, Boutayeb S, Majbar MA. Preparing African anticancer centres in the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e237.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souadka A, Essangri H, Benkabbou A, Amrani L, Majbar MA. COVID-19 and Healthcare worker's families: Behind the scenes of frontline response. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souadka A, Essangri H, El Bahaoui N, Ghannam A, El Ahmadi B, et al. CRS and HIPEC: Best model of antifragility in surgical oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2022;126:396-397.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souadka A, Majbar MA, El Harroudi T, Benkabbou A, Souadka A. Perineal pseudocontinent colostomy is safe and efficient technique for perineal reconstruction after abdominoperineal resection for rectal adenocarcinoma. BMC Surg. 2015;15:1-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vassalou L. The learning organization in health‐care services: Theory and practice. J Eur Ind Train. 2001;25:354-365.

- Weldy TG, Gillis WE. The learning organization: Variations at different organizational levels. Learn Org. 2010;17:455-470.